|

Hello! This journal club we reviewed the PED sickle cell with fever protocol. Below are the highlights from that protocol that we found to be the most important steps of the protocol that also had some evidence behind them in the articles listed below. (BTW in the first article Gibbs is one of the authors!) Hope you enjoy! - Kat

0 Comments

Hey everyone, This year the PEM fellows have decided to do PEM Journal club a little differently from last year. Periodically we will critically appraise the evidence behind the clinical protocols that we currently use in our Pediatric ED to better understand why we do what we do. For our first protocol, we reviewed the new Peds ED Asthma Pathway. Below are the take home points for the main topics that we discussed. Enjoy! - Kat Bryant Dexamethasone vs Prednisolone:

PEM Fellows Journal Watch Quarterly

Your Up-to-date summaries of relevant pediatric emergency medicine literature from the comfort of your home Editor – Jeremiah Smith Columnists Christyn Magill JR Young Kat Bryant Simone Lawson All Articles are archived @ http://www.cmcedmasters.com/pem-journal-watch.html December January Synopsis – This study compared career preparation and potential attrition of the PEM workforce with a prior assessment done in 1998. This was performed via an email sent to members of the AAP SOME and non-AAP members board certified in PEM. 2,120 surveys were sent and 895 individuals responded (40.8%). 53.7% were female which was up from 44% in 1998. 62.9% practiced in a free-standing children’s hospital and 60% of their time was spent in direct patient care. Nearly 50% spent time in research and 50% performed other activities like EMS, disaster medicine, child abuse, etc. 21.3% had dedicated time for quality/safety. 95.6% felt fellowship prepared them well for clinical care but felt less prepared for research (49.2%) and administration (38.7%). 46% plan to change to clinical activity within 5 years. 88.5% of respondents reported feelings of burn out at work or callousness toward people as a result of work (67.5%) at least monthly. 1 in 5 reported these feelings weekly. They concluded that many were satisfied with fellowship preparation for professional activities but there are gaps remaining in training for nonclinical activities. They also felt that burnout is prevalent and there is likely to be substantial attrition of PEM providers in the near future. Gorelick M, Schremmer R, Ruch-Ross H, et al. Current Workforce Characteristics and Burnout in Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23:48-54 Synopsis - Acute pain is commonly under treated in children. Studies have also shown in adults disparities in analgesia in different races and ethnicities. This study in Israel assessed if there were disparities between Arabic and Jewish children for opioid analgesia for acute pain, specifically in fractures and dislocations. Over a 4 year period this retrospective cohort study collected pain assessments and opioid analgesia given by Jewish nurses to both Jewish and Arabic children. This study found no difference in treatment in the two groups, suggesting ethnicity has no effect on opioid analgesia in acute pain in this pediatric ED. Shavit I, Brumer E, Shavit D, et al. Emergency Department Pain Management in Pediatric Patients with Fracture or Dislocation in a Bi-Ethnic Population. Ann Emerg Med 2016;67:e1 9-14 Synopsis: This study reviewed Poison Control Center data over a 10-year period to characterize the epidemiology of drug exposures amongst children 0-6 months of age, with the goal of therefore offering better preventative strategies based on presentation characteristics. Results indicate that unintentional drug exposures are common, and the majority of exposures are clinically benign. The PCC network is vastly underutilized, thereby increasing direct presentation to the ED. Improved anticipatory guidance is recommended, but what other strategies should we consider to prevent inappropriate ED referrals? An Evidence-Based Approach to Minimizing Acute Procedural Pain in the Emergency Department and Beyond. Samina A, McGrath T, Drendel A. An Evidence-Based Approach to Minimizing Acute Procedural Pain in the Emergency Department and Beyond. Ped Emerg Care 2016;32:36-42 Synopsis – This was a review article intended for emergency medical providers for children aimed at familiarizing clinicians with pediatric pulmonary hypertension. They reviewed pathophysiology, clinical presentation, initial diagnostic strategies, basic chronic management, and management of pulmonary hypertensive crisis. Del Pizzo J, Hanna B. Emergency Management of Pediatric Pulmonary Hypertension. Ped Emerg Care 2016;32:49-55 February Synopsis – As we know, nonvisualization of the appendix often presents a diagnostic dilemma in the emergency department. Their primary aim was to quantify the accuracy of MRI and US in the setting of a nonvisualized appendix. They also reported the sensitivity of MRI and US and correlation between the two imaging modalities. They retrospectively reviewed all pediatric emergency department patients aged 3-21 years who underwent a MRI (N = 205) and/or US (N= 583) for the evaluation of appendicitis. They had 589 included patients with 146 having appendicitis. If the appendix was nonvisualized with no secondary signs of appendicitis, MRI had an accuracy of 100% and US was 91.4%. If it was nonvisualized but had secondary signs of appendicitis, MRI had an accuracy of 50% and US was 38.9%. There was moderate correlation between the two (0.573). They concluded that if MRI is used but the appendix is not visualized, MRI is effective at excluding appendicitis if there are no secondary signs though less helpful if there are secondary signs of appendicitis. It appears to be somewhat more useful than a non-diagnostic US with or without secondary signs of appendicitis. In addition, 8.6% of patients with a nonvisualized appendix had appendicitis. Kearl Y, Claudius I, Behar S, et al. Accuracy of Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Ultrasound for Appendicitis in Diagnostic and Nondiagnostic Studies. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23:179-185 Synopsis - This study evaluated the retention for PALS/NRP protocols and procedures at 6wks, 18wks and 52wks after an initial training simulation session. They found that there was a predicted variable initial score/retention score for different experienced practitioners; but in all levels of experience the retention/competency scores decreased as time passed showing that retraining/refresher intervals would be helpful to maintain important PALS/NRP skills. Andreatta P, Dooley-Hash S, Klotz J, et al. Retention Curves for Pediatric and Neonatal Intubation Skills after Simulation-Based Training. Ped Emerg Care 2016;32:71-76 Synopsis – This was the results of an electronic questionnaire distributed to urgent care center administrators. An urgent care center was identified by the American Academy of Urgent Care Medicine directory. They found the most common diagnoses reported were otitis media, URI, strep pharyngitis, bronchiolitis, and extremity sprain/strain. Seventy-one percent have contacted EMS for transport of a critical ill or injured child within one year. Urgent care centers had the reported availability of the following essential medications and equipment: oxygen source (75%), nebulized inhaled β-agonist (95%), intravenous epinephrine (88%), oxygen masks/cannula (89%), bag-valve mask resuscitator (81%), suctioning device (60%), and AED (80%). Centers reported the presence of the following written emergency plans: respiratory distress (40%), seizures (67%), dehydration/shock (69%), head injury (59%), neck injury (67%), significant fracture (69%), and blunt chest or abdominal injury (81%). Only 47% performed formal case review in a QI format. Wilkinson R, Olympia R, Dunnick J, et al. Pediatric Care Provided at Urgent Care Centers in the United States: Compliance with Recommendations for Emergency Preparedness. Ped Emerg Care 2016;32:77-81 Synopsis: Pain control makes sense. The majority of papers reviewed agree with this. This paper has no METHODS section, fails to even mention the data surrounding clinical practice guidelines until the next to last paragraph, and generally speaks in broad terms without specific details. The paper relies heavily on Cochrane reviews without digging further. It suggests that clinical practice guidelines are validated to help improve overall efficacy, but the studies they reference are for neonates or post-operative pain control, not specific the pediatric patients in the ED. It appears that common sense wins out (pain control is important and humane), but that people need to utilize it – meaning that we need to remember the importance of analgesia, and therefore prioritize it, rather than think of it as an afterthought. Kang M, Brooks D. US Poison Control Center Calls for Infants 6 Months of Age and Younger. Pediatrics 2016;137:1-7 Synopsis – This statement updated previous recommendations with new evidence on the prevention, assessment, and treatment of neonatal procedural pain. This important because the prevention of pain in neonates should be the goal of all healthcare professionals tasked with their medical care. Preterm infants in the NICU are not only at the greatest risk of neurodevelopmental impairment but are also exposed to the greatest number of painful stimuli in the NICU. There is a paucity of literature regarding how to effectively and safely treat their pain. What has been proven and studied is underused for routine but painful procedures. They recommend that every health care facility caring for neonates should: implement a pain-prevention program with strategies to minimize the number of painful procedures performed and a pain assessment and management plan including both assessment, pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic, and measures to minimize pain with surgery and major procedures should be implemented. Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine. Prevention and Management of Procedural Pain in the Neonate: An Update. Pediatrics 2016;137:1-13 March Synopsis – This is a queried report from an emergency medicine e-mail discussion list and social media allergy group to identify injuries in children as the result of epinephrine autoinjector use. Twenty-two cases were described. Twenty-one of these were during intentional use. Seventeen children experienced lacerations, four resulted in the needle being stuck in the child’s limb, and one resulted in a laceration to a nurses’ finger. In six cases the operator was a health care provider, fourteen cases by the patient’s parent, and one by the patient. They concluded that these are obviously lifesaving devices in the management of anaphylaxis but injury such as laceration can occur. Minimizing injection time, improving device design, and providing leg immobilization instructions may decrease risk of injury. Brown J, Tuuri R, Akhter S, et al. Lacerations and Embedded Needles Caused by Epinephrine Autoinjector Use in Children. Ann Emerg Med 2016;67:307-315 By Christyn Magill MD CC: infant vomiting HPI: 2mo term female, born at 38 weeks gestation, SVD, no complications, normal prenatal labs. Presents with 3 days of projectile vomiting about 10-15 minutes after feeds. Initially vomitus appeared to be regurgitated food. Now, vomitus is darker in color, but no bright red blood, non bilious. Decreased UOP. Normal bowel movements per parents. Normal energy. Acting hungry. Parents deny fevers, sick contacts, rashes, diarrhea. Vomiting seems to bother child and gets fussy, but acts normally in between feeds. This is a first child for the family. Physical Exam: VS: T 98.6F rectal, HR 135, BP 114/74, RR 44, O2 98% on RA GENERAL: Laughs and smiles, very active in the ED, not clinically dehydrated HEENT: PERRL, EOMI, moist mucous membranes, no icterus, TM's NL, Oral-pharynx NL, nares NL CHEST: Normal S1 and S2, no murmurs, lungs clear to auscultation ABD: Tenderness-none, no HSM, bowel sounds NL Rectal: normal tone, small amt stool in vault, Hemoccult-positive stool BACK: Non tender, no costovertebral angle tenderness EXTREMITY: Normal active full ROM throughout all extremities, no tenderness, appearance normal GU: Normal external female genitalia SKIN: No pallor/rashes, warm & moist, brisk cap refill NEURO: Good suck, grasp, makes eye contact, social smile, +Moro reflex, Gross motor normal, gross sensation intact LYMPH: No lymphadenopathy What is on your differential diagnosis? What is your highest suspicion? What studies would you do on this patient in the ED? The following studies were done: VBG: pH 7.418, PCO2 28.8, PO2 49, Lactate 2.87, HCO3 18.6, Base deficit 5 Urine dip: glu-neg, bili-neg, ketones-large (80), SG-1.030, pH 6.0, prot-1+, urobil-normal, nitrate- neg, leuk-neg CBC: WBC 13.4K, Hb 10.9, Hct 32%, Plt 430 Chem8: Na 137, K 4.8, Cl 103, CO2 18, BUN 10, Cr <0.2, Glu 90 Hepatic: TProtein 5.4, Albumin 4.0, TBili 1.2, Dbili 0.2, Alk Phos 344, ALT 24, AST 34 CRP <0.5 Imaging: What is your diagnosis based on these studies? What is your management? Diagnosis: Necrotizing Enterocolitis Clinical Question: How do I recognize this in the emergency department, and what do I do about it? Helpful hint: http://pedemmorsels.com/necrotizing-enterocolitis/ Discussion:[1, 2]

Pathology

Epidemiology- Often, but not always, the term babies who develop NEC have some sort of underlying abnormality.[4-6]

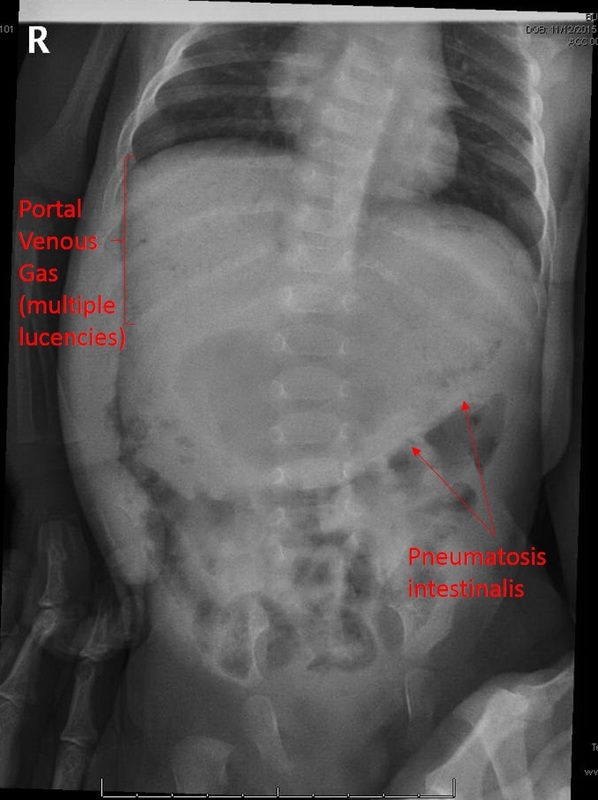

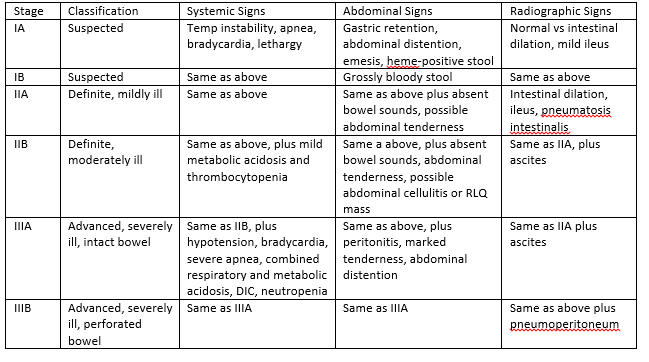

Usually presents earlier in term babies- In one retrospective study done by Sharma et al, the extremely premature infants presented with symptoms of NEC an average of 22 days of life, whereas the term babies had symptoms an average of 3 DOL. But this is not always true, as was the case with our baby above. Symptoms/Stages Modified Bell’s Criteria From Up To Date: Workup[2]

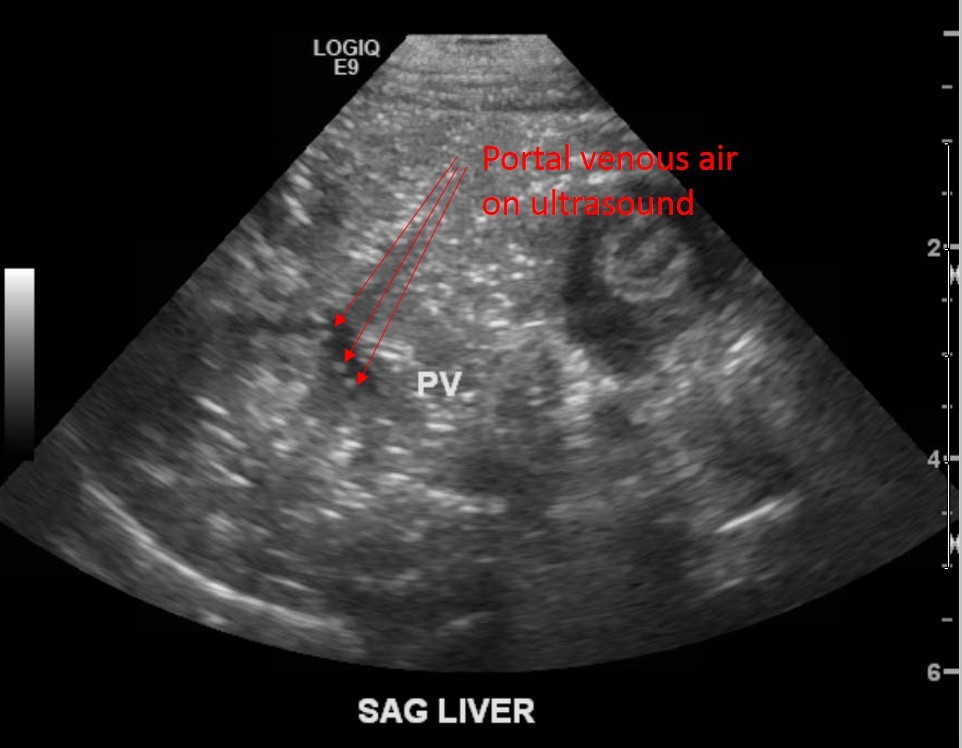

CBC plus diff, BMP, LFTs (if more advanced stages), VBG Thrombocytopenia, metabolic acidosis, hyperglycemia are trended for worsening disease. Plain films- upright and lateral decubitus to eval for free air, pneumatosis intestinalis, portal venous gas. RUQ Ultrasound to show portal venous gas. [7] Treatment[8] Medical- Antibiotics, bowel rest, supportive care, lab and radiologic monitoring. Antibiotic possible regimens (from UTD): ●Ampicillin, gentamicin (or amikacin), and metronidazole ●Ampicillin, gentamicin (or amikacin), and clindamycin ●Ampicillin, cefotaxime, and metronidazole ●Piperacillin-tazobactam and gentamicin (or amikacin) ●Vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and gentamicin ●Meropenem *Vancomycin instead of Ampicillin if in high MRSA area *Add Fluconazole if worried about fungal infection Surgical[9, 10]

Complications[6, 11] Acute- sepsis, meningitis, peritonitis, abscess formation, DIC, hypotension, shock, respiratory failure, hypoglycemia, metabolic acidosis Late- intestinal stricture, short gut syndrome *intestinal strictures in 9-36%, not significantly related to medical vs surgical treatment, drain vs laparotomy, gestational age, pneumatosis intestinalis. Term infants- 3% risk of NEC, 16% mortality. Updates Probiotics are now being studied for protective potential. [5] Back to our patient:

Clinical Pearls for ED:

References: 1. Sakellaris, G., et al., Gastrointestinal perforations in neonatal period: experience over 10 years. Pediatr Emerg Care, 2012. 28(9): p. 886-8. 2. Solomkin, J.S., et al., Diagnosis and management of complicated intra-abdominal infection in adults and children: guidelines by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis, 2010. 50(2): p. 133-64. 3. Sharma, R., et al., Impact of gestational age on the clinical presentation and surgical outcome of necrotizing enterocolitis. J Perinatol, 2006. 26(6): p. 342-7. 4. Short, S.S., et al., Late onset of necrotizing enterocolitis in the full-term infant is associated with increased mortality: results from a two-center analysis. J Pediatr Surg, 2014. 49(6): p. 950-3. 5. Terrin, G., A. Scipione, and M. De Curtis, Update in pathogenesis and prospective in treatment of necrotizing enterocolitis. Biomed Res Int, 2014. 2014: p. 543765. 6. Lambert, D.K., et al., Necrotizing enterocolitis in term neonates: data from a multihospital health-care system. J Perinatol, 2007. 27(7): p. 437-43. 7. Buonomo, C., The radiology of necrotizing enterocolitis. Radiol Clin North Am, 1999. 37(6): p. 1187-98, vii. 8. Barie, P.S., et al., A randomized, double-blind clinical trial comparing cefepime plus metronidazole with imipenem-cilastatin in the treatment of complicated intra-abdominal infections. Cefepime Intra-abdominal Infection Study Group. Arch Surg, 1997. 132(12): p. 1294-302. 9. Flake, A.W., Necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants--is laparotomy necessary? N Engl J Med, 2006. 354(21): p. 2275-6. 10. Moore, T.C., Successful use of the "patch, drain, and wait" laparotomy approach to perforated necrotizing enterocolitis: is hypoxia-triggered "good angiogenesis" involved? Pediatr Surg Int, 2000. 16(5-6): p. 356-63. 11. Schwartz, M.Z., et al., Intestinal stenosis following successful medical management of necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr Surg, 1980. 15(6): p. 890-9. By Dr. Kathleen Bryant

CC: Fever HPI: A 19 month old AA female presents with fever (Tmax 38.7*C) for 36 hours. Mom reports giving Tylenol/Motrin for fever control. Mom denies N/V/D, change in PO intake or change in UOP. Mom reports mild cough and nasal congestion. Immunizations UTD, no sick contacts. Physical Exam: VS: T: 38.7*C RR 16 HR 110 BP 110/80 Gen: well appearing, sitting in NAD HEENT: bilateral TMs clear, no middle ear effusion, mild nasal congestion, posterior oropharynx clear, no cervical lymphadenopathy CV: mild tachycardia, no M/G/R, capillary refill brisk, 2+ peripheral pulses Resp: CTAB, no W/R/R Abd: NTND, +BS, soft GU: normal genitalia, no rashes Discussion: No source of infection is identified in this patient. Do we need to obtain an urinalysis to rule out an UTI? Why do we care about UTIs? What is the significance of missed or delayed treatment of UTIs in this patient population?

Clinical Pearls for ED:

Author: Dr. Kathleen Bryant References: 1. Roberts, K.B., Revised AAP Guideline on UTI in Febrile Infants and Young Children. Am Fam Physician, 2012. 86(10): p. 940-6. 2. Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infection, S.C.o.Q.I., Management, and K.B. Roberts, Urinary tract infection: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of the initial UTI in febrile infants and children 2 to 24 months. Pediatrics, 2011. 128(3): p. 595-610. To Tap or Not to Tap, That is the Question: At Least When it comes to Complex Febrile Seizure12/16/2015 CC: Seizure HPI: This is a fully vaccinated 18 month female here after seizure activity at home. Mom states she has had three episodes of generalized tonic-clonic activity in the last 12 hours. After her first episode, mom states her temperature was 103.4F and has improved with anti-pyretics but returns and she has had two additional episodes of tonic-clonic movement. Both upper and lower extremities are involved equally and the episode lasts for 60-90 seconds with spontaneous resolution. She has been sleepy afterwards and then acts more normal but is fussier than usual if the fever doesn’t come down. Her last episode was 1 hour ago. She has had no recent trauma, no focal abnormalities, and has otherwise been acting normal until today. She last received acetaminophen 2 hours ago. Physical Exam: T 99F P 130 RR 25 O2 100% Gen: Is sitting in mom’s lap watching her iphone. NAD, though she is fussy when you examine her ears, she is appropriately consolable by mom afterwards HEENT: Bilateral TMs normal without erythema or bulge, oropharynx is normal without lesions or erythema, tonsils are normal in appearance without exudate, copious mucoid drainage from nose Neck: Moving in all directions CV: S1S2, RRR, no murmurs, gallops, or rubs Lung: Transmitted upper airway sounds but no wheezes or rales, no focal lung findings Abdomen: soft, non-tender, non-distended, no HSM, normal bowel sounds Musculoskeletal: No focal tenderness in extremities Lymph: mild cervical lymphadenopathy Neurologic: Appropriately consolable, acting at baseline per mom now, walking normal, moves all extremities appropriately with normal muscle tone, no altered mental status, smiles at you before you attempt to exam Discussion: This is a difficult case that we have all likely seen or will definitely see sometime (likely multiple times) in our career. I have intentionally left out the work-up and management of this case because that is what I want to discuss. This is a typically appearing 18 month old with a fever. She is fussy with examination but appropriately consolable by mom like many of our children with viral infections. The difference here is she has had what appears to be complex febrile seizures (three seizures within 24 hours) but is now back at baseline and didn’t appear to have a prolonged post-ictal period. She is fully vaccinated but this is still a presentation that should concern all of us. So what do you do? We are emergency medicine physicians and we are trained to worry about bad things. The biggest thing on all of our minds should be: “do I need to worry about meningitis in this girl (or other pathology but we are focusing on meningitis for this discussion)?” Unfortunately, there are no consensus guidelines to make our job easy with this one. Let’s cover the low-hanging fruit first. If this child was still post-ictal, not acting herself per mom, required intubation, required multiple AEDs to stop seizure (i.e. febrile status epilepticus), or had abnormalities on her exam now, she’d get a full septic work-up, antibiotics, and admission along with possible imaging. This case isn’t that easy though. Febrile seizures affect 2-5% of children aged 6 months – 6 years. 25-30% of these febrile seizures may be classified as a complex febrile seizure. There is also considerable variation within what classifies a child as having had a complex febrile seizure. The child who had two very brief simple appearing febrile seizures within the same 24hr time period is different than the child with prolonged seizure who has failed to return to baseline. Often times, clinical judgment and personal experience comes into play with these variable presentations since there are no consensus guidelines for management. Despite this variable presentation, our job is to think about bad things. The bad thing we are concerned about with this child is acute bacterial meningitis. There is decreasing prevalence of bacterial meningitis but it hasn’t been eliminated. There are small studies looking at this exact question and most say the same thing, “routine CSF testing is likely not necessary in an otherwise well appearing child without any abnormalities back at baseline but absolutely necessary if additional findings on exam, incomplete antibiotic administration, or unvaccinated.” Najaf-Zadeh et al performed a systematic review and meta-analysis in 2013 found the pooled prevalence of ABM in children with complex febrile seizures to be 0.6% (95% CI 0.2-1.4) but this was derived from only two studies. The overall prevalence of bacterial meningitis in children who had a seizure and fever was frighteningly 2.6% (95% CI 0.9-5.1). Studies evaluating for acute bacterial meningitis with complex febrile seizure Green et al 1993 111 children with ABM and seizure 103 comatose or obtunded at presentation Remaining 8 had abnormal neuro exam or nuchal rigidity Kimia et al 2010 526 children 3 with ABM Two children with ABM had AMS at presentation One had contaminated CSF Cx but grew strep in blood Teach and Geil 1999 243 children 11% with complex febrile seizures None had ABM Setz et al 2009 390 children 6 with ABM 1 with HSV encephalitis (0.3%) All had AMS on presentation Casasoprana et al 2013 157 children 3 ABM but all with complex febrile seizure Incidence of ABM 1.9% Additional clinical symptoms strongly associated with ABM Fletcher and Sharieff 2013 193 patients 1 with ABM (0.5%) None of the 43 children with two brief febrile seizures had ABM Hardasmalani and Saber 2012 71 Children 1 with ABM That patient had febrile status epilepticus So I ask you again, would you perform a lumbar puncture in this child? My personal opinion (and I highly recommend and expect deviation from this): I do not believe I would perform a lumbar puncture in this child but I wouldn’t discharge her home despite appearing well. She is normal appearing on examination now and despite the studies being small and underpowered to really answer the question, most are consistent that children with complex febrile seizure who ultimately have ABM have additional clinical findings (large caveat for this patient is that she is fully vaccinated). Obviously I would not start antibiotics on this patient but I am completely uncomfortable with the thought of discharging her home with complex febrile seizures nor am I a fan of performing a lumbar puncture and discharging home if the cell count is reassuring (culture is my gold standard and I’m sticking to it). If I had hesitated for one second and felt this child just wasn’t acting right to me or if the mom was insistent that she wasn’t right to her, I’d err on the side of lumbar puncture and treatment. Interestingly, a survey of 353 pediatric emergency medicine physicians and fellows in 10 US hospitals showed only 34% would perform a lumbar puncture in a child with complex febrile seizure. That is significantly lower than expected. By Jeremiah Smith, MD References: Casasoprana A, Hachon Le Camus C, Claudet I, et al. Value of Lumbar Puncture after a First Febrile Seizure in Children Aged Less than 18 months. A Retrospective Study of 157 Cases. Arch Pediatr 2013;20:594-600 Fletcher E, Sharieff G. Necessity of Lumbar Puncture in Patients Presenting with New Onset Complex Febrile Seizures. West Journ of Emerg Med 2013;14:206-211 Green S, Rothrock S, Clem K, et al. Can Seizures be the Sole Manifestations of Meningitis in Febrile Children. Pediatrics 1993;92:527-534 Hardasmalani M, Saber M. Yield of Diagnostic Studies in Children Presenting with Complex Febrile Seizures. Pediatr Emerg Care 2012;28:789-791 Hofert S, Burke M. Nothing is Simple About a Complex Febrile Seizure: Looking Beyond Fever as a Cause of Seizures in Children. Hosp Pediatr 2014;4:181-187 Kimia A, Ben-Joseph E, Rudloe T, et al. Yield of Lumbar Puncture Among Children Who Present With Their First Complex Febrile Seizure. Pediatrics 2010;126:62-69 Kowalsky R, Jaffe D. Bacterial Meningitis Post-PCV7: Declining Incidence and Treatment. Pediatr Emer Care 2013;29:758-769 Najaf-Zadeh A, Dubos F, Hue V, et al. Risk of Bacterial Meningitis in Young Children with a First Seizure in the Context of Fever: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLOSOne 2013;8:e55270 Seltz L, Cohen E, Weinstein M. Risk of Bacterial or Herpes Simplex Virus Meningitis/Encephalitis in Children with Complex Febrile Seizures. Pediatr Emerg Care 2009;25:494-497 Teach S, Geil P. Incidence of Bactermia, Urinary Tract Infections, and Unsuspected Bacterial Meningitis in Children with Febrile Seizures. Pediatr Emerg Care 1999;15:9-12 PEM Fellows Journal Watch Quarterly

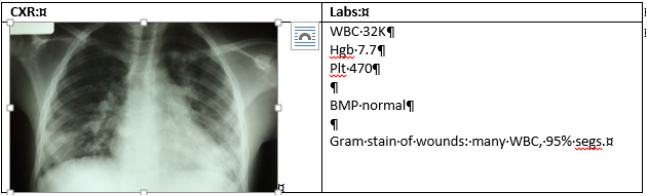

Your Up-to-date summaries of relevant pediatric emergency medicine literature from the comfort of your home Editor-in-Chief – Jeremiah Smith Columnists Christyn Magill JR Young Kat Bryant Simone Lawson All Articles are archived @ http://www.cmcedmasters.com/pem-journal-watch.html September “How many papers can you get out of one PECARN study…” Synposis – This was a planned subanalysis of a prospective, multicenter observational study of children ≤ 18 years of age with blunt torso trauma conducted in 20 EDs in the PECARN. They had clinicians document their suspicion for the presence of intra-abdominal injuries needing acute intervention (defined as death due to abdominal injury, surgical intervention, angiographic embolization, blood transfusion secondary to intra-abdominal hemorrhage, or IV fluids x2 nights in patients with pancreatic or GI injury) as < 1% (low-risk), 1-5%, 6-10%, 11-50%, or >50% prior to knowledge of abdominal CT scanning. Their total population was 11,919 patients. IAI undergoing acute intervention was diagnosed in 203 (2%) of patients. Abdominal CT scans were obtained in 2,302/2,667 (86% 95% CI 85-88%) with clinician suspicion ≥ 1% and in 3,016/9252 (33% 95% CI 32-34%) with clinician suspicion <1%. Sensitivity and specificity of the clinical decision rule for IAI requiring acute intervention was 97% (95% CI 76.9-87.7%) and 42.5% (95% CI 41.6-43.4%) compared to 82.8% (95% CI 76.9-87.7%) and 78.7% (95% CI 77.9-79.4%) for clinician suspicion. 35 (0.4%) of patients with a clinician suspicion of <1% had IAI requiring acute intervention. They concluded that the derived clinical decision rule had a significantly higher sensitivity but a lower specificity than clinician suspicion for IAI undergoing acute intervention. They also concluded that the higher specificity that clinician suspicion had did not translate into clinical practice because clinicians frequently obtained abdominal CTs in patient they considered low-risk. Mahajan P, Kupperman N, Tunik M, et al. Comparison of Clinical Suspicion Versus a Clinical Prediction Rule in Identifying Children at Risk for Intra-Abdominal Injuries After Blunt Torso Trauma. Acad Emerg Med 2015;22:1034-1041 “Is it necessary for me to drink my own urine? No, but I do because it’s sterile and I like the taste.” Patches O’Houlihan Synopsis – Contrary to what the great Patches O’Houlihan thinks, urine is not always sterile, especially in 2-12month febrile infants with bronchiolitis according to a recent article in Pediatric Emergency Care. Elkhunovich and Wang performed a prospective cohort study enrolling a convenience sample of febrile infants aged 2-12months with bronchiolitis who presented to the emergency department. They were able to enroll 90 patients who had a fever >38°C and had urinalysis and/or urine cultures ordered. Using the new AAP guidelines for diagnosis of UTI (requires pyuria or nitrites on UA plus >50,000colonies on UCx) they found 4.5% (95% CI 1.2-11%) had a UTI and using just UCx 6.7% (95% CI 2.5-13.9%). Small sample size and a predominance of uncircumsized latino males is a large limitation of this study but it is interesting nonetheless. Elkhunovich M, and Wang V. Assessing the Utility of Urine Testing in Febrile Infants Aged 2 to 12 Months with Bronchiolitis. Pediatr Emer Care 2015;31:616-620 “CRP later gator ” Synopsis - This paper evaluated reduction in ED LOS by implementing standard bedside CRP testing in previously healthy, now febrile children, presenting to a large Pediatric ED in the Netherlands. Although sophisticated multivariable linear regression modeling and propensity scoring showed a 12 minute decrease in LOS, significant differences in practice patterns and lack of a proven clinical benefit (morbidity and mortality or ED return visits) make this intriguing, but not clinically relevant at this time in our setting. Nijman RG, Moll HA, Vergouwe Y, Rijke YB, Oostenbrink R. “C-Reactive Protein Bedside Testing in Febrile Children Lowers Length of Stay at the Emergency Department” Pediatric Emergency Care. 2015;31:633-39 “In other news, hospital admissions for “hypoxia” are soaring this year” Synopsis – This study enrolled healthy patients, ages 5-15, living at sea level, to determine normal oxygen saturations. The majority of patients were Caucasian, with a large Asian minority, and very few African Americans or Hispanics. No patient had an oxygen saturation less than 97%, suggesting that values of 95 and 96% are suggestive of pathology. That said, there is no data to demonstrate clinical significance of values < 97%. This study has limited applicability as ethnic variation and associated skin coloration may alter values and altitude can change baseline values. Informative for Caucasian pediatric patients who live at sea level. Limited clinical relevance. Elder JW, Baraff SB, Gaschler WN, Baraff LJ. “Pulse Oxygen Saturation Values in a Healthy School-Aged Population.” Pediatric Emergency Care. 2014;31:645-47 “Maple syrup urine disease makes me think of pancakes….” Synopsis – This was a review article designed to give emergency room providers an understanding of the history of newborn screening programs and what is commonly screened. It also provided information regarding the clinical setting where suspicion for a metabolic or genetic disorder should be high in a newborn patient and what the future directions are for these screening programs. Lavin L, Higby N, Abramo T. Newborn Screening: What Does the Emergency Physician Need to Know? Pediatric Emergency Care. 2015;31:661-669 October “This just in, people don’t always follow-up. In other news..” Synopsis – This was a retrospective case-control study to determine if specific demographic and clinical factors are associated with aftercare compliance in a population of publicly insured patients with forearm fractures. They found that 68.2% of patients received timely orthopedic after care, 17.5% received delayed aftercare, and 14.3% had no documented aftercare. Patients that were younger and received orthopedic intervention in the ED were more likely to have timely orthopedic aftercare. Older patients and those who did not require orthopedic intervention in the ED were less likely to have timely orthopedic follow-up. Only 77.3% of patients with severe forearm fractures had timely follow-up. There was no association between gender of patient or race. Jamal N, Iqbal S, Ryan L. Factors Associated with Orthopedic Aftercare in a Publicly Insured Pediatric Emergency Department Population. Pediatr Emer Care 2015;31:704-707 November “Nothing funny about this one” Synopsis – This was a qualitative research design that used one-on-one interviews to understand general ED providers’ experiences with child abuse and neglect. Consistent with grounded theory, they coded the transcripts and collectively refined and identified themes for analysis. They found that barriers to recognizing child abuse and neglect included: providers’ desire to believe the caregiver, failure to recognize that a child’s presentation could be due to child abuse, challenges innate to working in an ED, and provider biases. Barriers to reporting included: factors associated with the process of reporting, lack of follow-up of reported cases, and negative consequences of reporting such as testifying in court. Facilitators were: real-time case discussion with peers or supervisors and belief that it was better for patient to report in suspicious settings. Tiyyagura G, Gawel M, Koziel J, et al. Barriers and Facilitators to Detecting Child Abuse and Neglect in General Emergency Departments. Ann Emerg Med 2015;66:447-454 “J-tips for everyone!” Synopsis – This was a randomized single-dose clinical trial comparing the efficacy of the J-Tip device to vapocoolant spray for reduction of venipuncture pain in young children. 205 children were enrolled and randomized into one of 3 groups: J-tip, vapocoolant (standard of care at their institution), or NS J-tip with vapocoolant in a ratio of 2:1:1. The encounters were videotaped from start to finish, divided into 3 times (before intervention, after intervention, and during venipuncture), and each video was scored (scorers blinded to intervention) individually based on a pain-scoring protocol. All groups had increased pain from baseline to venipuncture overall and they stated they were unable to control for patient anxiety. There was no change in pain from intervention to needle stick with J-tip (i.e. J-tip numbed the skin) and a significant change in pain from intervention to needle stick with vapocoolant and sham J-tip (i.e. didn’t work as well as J-tip). They concluded that the J-tip worked to decrease pain with no decrease in venipuncture success rates. Lunoe M, Drendel A, Levas M, et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Jet-Injected Lidocaine to Reduce Venipuncture Pain for Young Children. Ann Emerg Med 2015;66:466-474 “Figuring out who needs to go home in a C-collar is a real pain in the neck…. “ Synopsis – Children’s anatomy makes severe cervical injuries rare but unfortunately leads to diagnostic conundrums when they have persistent midline tenderness with negative imaging. The NEXUS pediatric study found midline tenderness to be the most common abnormality as well (39.2%). This was a single center retrospective study looking at children aged 1-15 years who were discharged home in a rigid cervical spine collar (standard of care at Boston Children’s at the time) after blunt trauma over a 5 year time period. Their primary outcome of interest was clinically significant cervical spine injury and their secondary outcome was continued use of the collar after follow-up. They were able to find 307 subjects who met their inclusion criteria and 289 with follow-up information available. 65.4% had follow-up in a subspecialty spine clinic and 84.6% of those were able to discontinue the hard collar after that visit (average time to first visit was 10 days). 115 patients had repeat imaging at spine clinic (3.2% x-rays, 42.3% flexion-extension views, 2.1% CT, and 13.2% MRI). 10.1% were left in the collar due to persistent tenderness without findings on imaging and 2.1% had findings related to their trauma on imaging but none required surgical intervention. The major limitations of this study is that it is retrospective. Dorney K, Kimia A, Hannon M, et al. Outcomes of Pediatric Patients with Persistent Midline Cervical Spine Tenderness and Negative Imaging Result After Trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015;79:822-827 “If Dr. Sachdev was write we’ll never hear the end of it” Synopsis – This was a retrospective trauma registry analysis looking at healthy children 0 to 17 years of age who presented to a Level I tertiary care pediatric hospital with blunt trauma. Multivariable regression was used in an attempt to identify independent predictors of pelvic fracture. They included 1,121 patients and 87 (7.8%) had pelvic fracture. Predictors evaluated were: pain/abdnormal examination of pelvis/hip (OR 16.7 95% CI 9.6-29.1), femur deformity (OR 5.9 95% CI 3.1-11.3), hematuria (OR 6.6 95% CI 3.0-14.6), abdominal pain/tenderness (Not independently predictive but statistically significant), GCS ≤ 13 (OR 2.4 95% CI 1.3-4.3), and hemodynamic instability (OR 3.4 95% CI 1.7-6.9). 590 patients had none of these predictors and only 1 (0.2%) had pelvic fracture. 86 of 87 (OR 119.1 95% CI 16.6-833) with pelvic fracture had at least one predictor. They also found that if all children had pelvic radiographs obtained, this rule would stop 53% of radiographs. They concluded that children with blunt trauma without pain/abnormal examination of the pelvis/hip, femur deformity, hematuria, abdominal pain/tenderness, GCS ≤ 13, or hemodynamic instability constitute a low-risk population for pelvic fracture with a risk rate of < 0.5%. They felt that this population did not require routine pelvic imaging. Haasz M, Simone L, Wales P, et al. Which Pediatric Blunt Trauma Patients Do Not Require Pelvic Imaging? J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015;79:822-832 PEDIATRIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE BLOG Myositis Tropicans October 20, 2015 HPI: Previously healthy 14-yo M presents with fever, dyspnea, inability to bear weight, and draining abscess on left abdomen. Developed small abscess 1 week prior after seemingly negligible trauma, which older brother drained at home. Over next 5 days, developed inability to walk, spiking fevers, and severe dyspnea. No PMH. Lives at home with older brother. Both parents deceased. Physical Exam: Patient is sitting upright, severely distressed with tachypnea and heavily labored breathing. T 40, BP 110/70, HR 130s, RR 50s, SpO2 82% RA. Lungs: tachypneic with intercostal retractions and nasal flaring. Generally clear, but bibasilar diminished breath sounds. CV: tachycardic, hyperdynamic. Abdomen: distended and firm. Severe LLQ tenderness. Incised abscess on left abdomen with minimal active drainage, no erythema. Ext: severe pain with palpation of left thigh. Indurated. Pain with internal/external rotation. Unable to flex. Neuro: GCS 13-14. Clinical Course: HD 0: Formal incision and drainage of abdominal wound and empiric dicloxacillin. CXR as below. BiPAP. NS at 1.5 maintenance. Fever spikes > 39.5 despite drainage and antibiotics. HD 1: US of left hip/leg showed large abscess formation tracking upwards towards abdominal wound. I&D performed in OR. Continued fevers, now > 40. Antibiotics changed to vancomycin and clindamycin. HD 2: Hypotensive (90s/40s) requiring numerous NS boluses. 48 hours post second I&D, respiratory status improving, but new left elbow pain. HD 4: US demonstrates intramuscular abscess along proximal forearm. Taken to OR for I&D. HD 6: Blood pressure normalizing, fever curve improving. HD 8: Clinically improved. However, recurrent fever and mild left-sided chest pain and tachypnea. US shows left-sided pulmonary abscess. Surgical drainage planned. Discussion: This patient presents with classic findings of myositis tropicans (MT). MT is a disease most commonly encountered in the tropics, but there has been a steady rise in temperate regions.1, 2 It is characterized by skeletal muscle inflammation that leads to intramuscular abscess formation. The most common culprit is Staphylococcus aureus, accounting for 90% of tropical cases and 75% of temperate cases .1 Pathogenesis occurs in three stages: 1) Invasive – pain +/- fever without systemic symptoms; 2) Suppurative – abscess formation and systemic symptoms; and 3) Late stage – bacteremia and septic shock.3 Risk factors for development include trauma or strenuous exercise, and most importantly, immunocompromise. Diagnosis includes abscess aspirate or muscle biopsy for culture. However, approximately 15-30% of aspirates are sterile.4 Blood cultures, although recommended, are only positive in 5-10% of cases.5, 6 Imaging modalities such as US or CT/MRI are useful. Laboratory evaluation typically shows leukocytosis with left-shift, anemia, and thrombocytosis. ESR is elevated. Treatment is aimed at staphylococcus, and empiric therapy is dicloxacillin. Immunocompromised patients have higher risk for poly-microbial infection and should be covered accordingly. Recurrent fever is common due to new foci of infection. Repeat examination for new abscesses and subsequent drainage is essential. Treatment continues until abscess is clean, leukocytosis normalizes, and patient is afebrile x 7 days, usually 4-6 weeks.

Clinical Pearls for ED: * Consider myositis tropicans in any patient presenting with muscle pain, fever, and leukocytosis o Higher suspicion in patients who are from the tropics – specifically sub-Saharan Africa, Caribbean, and Asia o High suspicion in immunocompromised – HIV, poorly controlled DM, chemotherapy * Late presentation is common. Must consider in septic/bacteremic patients with multiple abscesses * Persistent fever typically means missed foci of infection – look for new abscesses, especially in children that have been treated elsewhere and are newly presenting to the ED * Incision and drainage is essential once abscesses have developed References: 1. Christin L, Sarosi GA. “Pyomyositis in North America: case reports and review.” Clin Infect Dis, 1992; 15:668-77. 2. Bonafede P, Butler J, et al. “Temperate zone pyomyositis.” West J Med, 1992; 156:419-23. 3. Chauhan S, Jain S, Varma S, Chauhan SS. “Tropical Pyomyositis (myositis tropicans): current perspective.” Postgrad Med J, 2004; 80:267-70. 4. Shepherd JJ. “Tropical myositis, is it an entity and what is its cause?” Lancet, 1983;ii:1240-2. 5. Gambhir IS, Singh DS, Gupta SS, et al. “Tropical pyomyositis in India, a clinic-histopathological study.” J Trop Med Hyg, 192; 95:42-6. 6. Brown JD, Wheeler B. “Pyomyositis: report of 18 cases in Hawaii. Arch Intern Med, 1984; 288:300-5. Author - JR Young HPI: This is a full-term 2 week female infant here with 4 episodes of bright red blood mixed with her stool over 24 hours. Last episode occurred in the examination room. She has continued to breast feed well with no fevers, vomiting, weight loss, abdominal pair, or irritability. Birth History: Mom was 26yrs, G1P1. Birth weight 3.1 kg. SVD and GBS negative. Received vitamin K at birth. Born in hospital and had pre-natal care. All serologies negative. Physical Exam: Afebrile and all vital signs are within normal limits. Wt 3.2kg. Well appearing. Abdomen is soft, non-distended, non-tender with normal bowel sounds. No hepatosplenomegaly. Normal external female genitalia. No anal fissures/tears/skin tags visualized. Normal rectal tone. Stool in diaper is yellow and seedy with blood mixed throughout (guaiac positive). Mom has a normal breast exam without signs of fissures or active bleeding. Work-up:

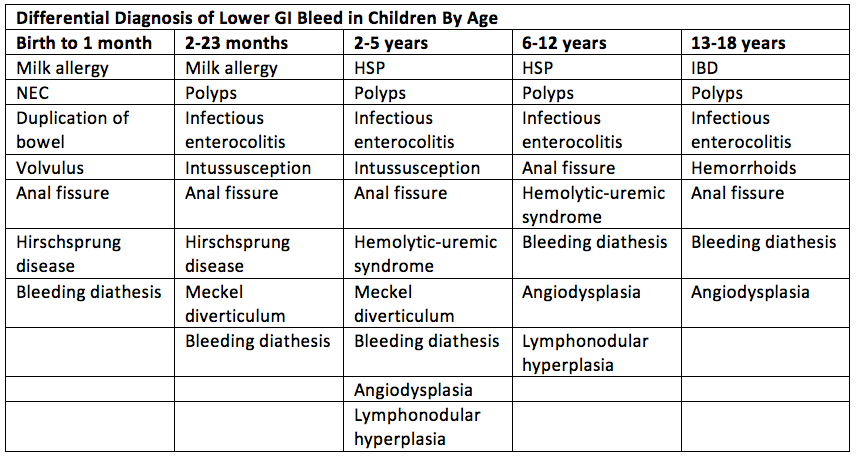

- Thorough history and physical exam o Age of patient o Diet o NSAID use o Color of blood (Bright red blood, maroon stools, dark tarry stools, etc) – i.e. is it upper GI or lower GI o Volume of blood and how often it occurs o Associated symptoms o Palpation of a polyp on rectal exam, anal fissures, anal tears? - Hemoccult (false-negative and false-positives are possible) – i.e. is it blood? - Apt-Downey test may help distinguish between fetal and maternal blood (swallowed blood during delivery or fissured maternal breast with feeding) - CBC with diff (and serial hemoglobin levels with admission) level - Consider coagulation studies, liver function tests, and stool evaluation (C. diff) - Cross and match if profuse bleeding - Consider supine, upright, and lateral decubitus abdominal radiographs to evaluate for air-fluid levels, dilated loops of bowel, pneumoperitoneum, or pneumatosis - Additionally radiographic imaging should be directed by your history and physical – i.e. an upper GI with small bowel follow-through if concerned about malrotation, ultrasound for possible intussusception, etc. Management: - Cardiopulmonary and fluid resuscitation as needed (with crystalloid or colloid as needed) - Consider a surgery consult if concern for surgical entity such as NEC - Consider broad-spectrum antibiotics if concern for an acute abdomen or sepsis - Consider NG tube placement for gastric decompression - Admission unless clear benign source and they have good follow-up - May require GI consult or hematology consult on admission as indicated Discussion: - Lower GI bleeds account for 30% of cases of GI bleeding presenting to the ED - Hematochezia is usually a manifestation of bleeding from the distal small bowel or proximal colon but can represent severe upper GI bleed - Often benign and self-limited but can represent serious illness and is very anxiety provoking in parents/physicians - Red Kool-Aid, red gelatin, fruit punch, tomato/cranberry juice, beets, peach skin, rifampin, medications with red syrup may lead to red appearing stool - Eosinophilia may indicate milk protein allergy - 10% of cases of necrotizing enterocolitis present in full-term infants and may present with non-specific symptoms and blood in the stool - Melena may occur with malrotation and volvulus when vascular compromise occurs – 10-20% of the time - 25% of patients with Hirschsprung related enterocolitis will present with blood in the stool - Changing to an elemental formula like alimentum or nutramigen if concerned about milk-protein allergy Patient Course This 2 week old was noted to have mild abdominal distention on re-examination and had an additional 3 episodes of hematochezia in the ED. A KUB with lateral decubitus view was ordered and radiology reported questionable signs of pneumatosis. Surgery was consulted who felt she was fussy and requested an abdominal ultrasound which was negative for intussusception. At that time, the patient was hospitalized with CHIPS and a surgical consult. Coagulation studies were obtained and she was found to have a greatly prolonged PT and aPTT. Hematology was consulted who recommended a coagulation work-up in addition to repeating the PT and aPTT. These were normal and it was felt the initial laboratory values were in error. GI was consulted as well and patient was ultimately discharged home with a diagnosis of milk-protein allergy and is doing well on an elemental formula. By Jeremiah Smith, MD References

PEM Fellows Journal Watch Quarterly Your up-to-date summaries of relevant pediatric emergency medicine literature from the comfort of you home Editor-in-Chief – Jeremiah Smith Columnists: Christyn Magill JR Young Kat Bryant Simone Lawson All Articles are archived @ http://www.cmcedmasters.com/pem-journal-watch.html Pediatrics

July “No, research isn’t a self-inflicted injury” Emergency Department Visits for Self-Inflicted Injuries in Adolescents Synopsis – This study analyzed the National Trauma Data Bank for the years 2009 to 2012 to examine trends in self-inflicted injury mechanisms and to identify factors associated with increased risk for self-inflicted injuries. ED visits for SII increased from 1.1% to 1.6% but self-inflicted firearm visits decreased from 27.3% to 21.9% though this was still the most common mechanism in males (females were cut/pierce). Odds of SII were higher in females, older adolescents, adolescents with comorbid conditions, and Asian adolescents but lower in African American adolescents. Adolescents with public or self-pay insurance had higher odds for SII than those with private insurance. If the adolescent had a history of previous SII, the odds of death from another injury is 12.9 (95% CI 6.78-24.6). "Anyone else realize that Chad could smile" Simulation in Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellowships Synopsis – This was a survey developed by consensus methods distributed to PEM program directors via anonymous online survey to describe the use of simulation and its barriers for implementation in PEM fellowship programs. They found that 97% of PEM fellowship programs use simulation-based training and the remaining 3% planned to use it within 2 years. The largest barriers to implementation seen were lack of faculty time, faculty simulation experience, limited support for learner attendance, and lack of established curricula. Most focus on resuscitation, procedures, and teamwork/communication. August “They should’ve looked at the OR for subtle nystagmus that only Randy can see” Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Intracranial Abnormalities in Unprovoked Seizures Synopsis – This was a 6-center prospective study attempting to determine the prevalence and risks factors associated with clinically relevant intracranial abnormalities in children with first time, unprovoked seizures. They found that 11.3% (95% CI 8%-14.6%) had clinically relevant intracranial abnormalities but only 0.8% (95% CI 0.1%-1.8%) required emergent/urgent intervention. Using logistic regression analysis, they found a high-risk past medical history had an OR of 9.2 (95%CI 2.4-35.7) and any focal aspect to seizure had an OR of 2.5 (95% CI 1.2-5.3). “Okay, now I understand why Chad was smiling” Quality Improvement Effort to Reduce Cranial CTs for Children With Minor Blunt Head Trauma Synopsis – This was a designed and implemented QI effort using an evidence-based guideline as well as individual feedback to decrease head CT use for children with minor head injuries. They had an initial head CT rate of 21% and had an absolute reduction of 6% (95% CI 3% - 9%) in head CT rates by implementing their evidence based guideline and an additional absolute reduction of 6% (95% CI 4%-8%) using individual provider feedback with providers continuing to order head CTs in children with minor head injuries. None of the children discharged from the ED required repeat admission within 72 hours of initial evaluation. “Every time a CG4 is ordered, an Emily rolls her eyes” Use of Serum Bicarbonate to Substitute for Venous pH in New-Onset Diabetes Synopsis – This is a retrospective study using linear regression to assess serum HCO3 as a predictor of venous pH and to classify severity of DKA. Using a HCO3 cutoff of <18 mmol/L had a sensitivity of 91.8% and specificity of 91.7% for detecting a pH <7.3 (used to diagnosis DKA). A HCO3 < 8 had a sensitivity of 95.2 % and specificity of 96.7 % for detecting a pH <7.1 (severe DKA). Pediatric Emergency Care July “Magill is from Florida, I’m just saying” Child Mental Health Services in the Emergency Department: Disparities in Access Synposis – This was a retrospective study using data from a publicly available deidentified data set to evaluate the use of the pediatric ED for mental health services in Florida. In Florida, 2.4% of all ED visits by children with Medicaid were for a psychiatric complaint though this is thought to be an understatement. Unsurprisingly, the uninsured and underinsured were more likely to use the ED for psychiatric issues. White children were found to use the ED for psychiatric complaints more often and the most common diagnosis was non-dependent drug abuse. Males were also more often to be evaluated in the ED for a mental health issue. “An electrifying read!” The Use of Automated External Defibrillators in Infants - A Report From the American Red Cross Scientific Advisory Council Synopsis - This was a retrospective literature review of the Cochrane Review and PubMed by the American Red Cross evaluating the sensitivity of AEDs for pediatric rhythms, accuracy of evaluation, and how often the AED advised shock when appropriate and when not appropriate. They also attempted to determine if there was a "toxic dose" of electricity when shock was applied since pediatric pads are not always readily available. VF was recognized accurately in 95-100% of cases with a sensitivity up to 100% but only 50-100% sensitivity for rapid VT (though small numbers in the case of 50% sensitivity). No shock was advised in non-shockable rhythms in 95-100%. Most AEDs also recognized SVT most of the time. Most studies showed 2J/kg to be sufficient for defibrillation unless the arrest was prolonged. Few studies evaluating proper dosage of electricity but a few studies showed myocardial dysfunction after biphasic shocks that normalized after 4 hours. August “Anyone care to show me where D2.5 is on the 90% page” Effects of Rapid Intravenous Rehydration in Children With Mild-to-Moderate Dehydration Synopsis - This was a prospective, observational, descriptive study in 2 tertiary care hospitals in Spain evaluating admission rates of children with mild to moderate dehydration after rapid IV bolus with 2.5% dextrose in the children's ED. IV rehydration was successful in 83.1% of patients but 16.8% required hospitalization for persistent vomiting. They did find a statistically significant decrease in the level of ketonemia and uremia but no change in sodium, chloride, potassium, or osmolarity values. “I still think a lollipop is better” Expedited Delivery of Pain Medication for Long-Bone Fractures Using an Intranasal Fentanyl Clinical Pathway Synopsis - This was initially a retrospective chart review looking at usage of intranasal fentanyl in the children's ED prior to protocol implementation. After this, they instituted a prospective single center study comparing intranasal fentanyl vs intravenous morphine. They found that 20% more patients who received intravenous morphine required a second dose vs 9% for intranasal fentanyl. A pain score decrease within 10 minutes was found in 14% of children receiving morphine and 26% with fentanyl but the study was underpowered for this outcome. There was a statistically decreased time to administration for fentanyl and a higher percentage of the fentanyl children were taken to the OR. Academic Emergency Medicine July “Is there anything ultrasound can’t do” Diagnostic Accuracy of Ultrasonography in Retained Soft Tissue Foreign Bodies: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Synopsis - This was a systematic review evaluating ultrasound characteristics (sensitivity and specificity) when evaluating for soft tissue foreign body. They found an overall sensitivity of 72% (95%CI 57-83%) and specificity 92% (95% CI 88-95%). They found that it had a sensitivity of 96.7% (95%CI 90-99.1%) and specificity of 84.2% (95%CI 72.6-92.1%) for a wooden foreign body. The articles had a high degree of heterogeneity (I2 90% 95%CI 80-100%). They found that the overall sensitivity and specificity found was equivalent or slightly better than history and radiograph. “Only Canada can have “after-hours” surgery” Variation in the Diagnosis and Management of Appendicitis at Canadian Pediatric Hospitals Synopsis - This was a multi-center retrospective chart review across 12 tertiary care Canadian hospitals evaluating practice variations around diagnosis and management of pediatric appendicitis in children admitted from an emergency department. The primary outcome evaluated was performance of appendectomy after hours (00:01-08:00) and secondary outcomes included: negative appendectomy rate, perforation rate, rate of laboratory or imaging studies, rate of analgesia use in ED, and rate of antibiotics use in ED. They found 13.9% (95%CI 7.1-21.6%) received after-hours surgery and the overall perforation rate was 17.4% but not associated with rates of after-hour surgery. ~97% of patients received CBC and 80% had a UA performed. CRP and BCx were performed in <20% of patients. Imaging was performed in 77.5% of patients and 67% of those were ultrasound and 3.6% were abdominal CT. >33% of children went to the OR for appendectomy without imaging and the negative appendectomy rate was 6.8%. Only 43% received narcotic pain control and 67% received antibiotics in the ED. There was considerable practice variability among all sites. “Real men of genius question that head CT use” Emergency Department Visits and Head Computed Tomography Utilization for Concussion Patients From 2006 to 2011 Synopsis - This was a cross-sectional analysis of the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) from 2006-2011 looking at the epidemiology of concussion and rates of head CT. They found a national incidence of concussion visits has increased 28.1% and is now 239 visits per 100,000 person-years. Head CT use has increased by 36% though overall injury severity decreased 66.4%. Patients discharged from the ED with a concussion increased from 78% to 87%. August “Pre-procedural checklist at bedside, check” Continuing Medical Education Activity in Academic Emergency Medicine Synopsis – This is a single center before-and-after evaluation of intubation related complications in trauma patients with the implementation of a pre-procedural checklist. They found 1.5% intubation-related complications during the post-checklist time period compared to 9.2% before the checklist was implemented. Adherence to safety measures also improved from 17.1% to 69.2%. Paralysis-to-intubation time decreased post-checklist though their IQRs did overlap. “Mmm, bacon” Ultrasound Accurately Identifies Soft Tissue Foreign Bodies in a Live Anesthetized Porcine Model Synopsis – This study inserted wood, metal, or glass foreign bodies into anesthetized pigs to examine the test characteristics of US for foreign body evaluation in living tissue and whether hematoma or edema improved diagnostic accuracy. Physical exam and radiographs miss up to 38% of retained foreign bodies but they found ultrasound had a sensitivity of 85-88% (95%CI 79-94%) and specificity of 83-86% (95%CI 73-98%). Two hours after placement of the foreign body, the sensitivity was 87% (95%CI 82-93#) and specificity was 89% (95%CI 81-97%) with only 8% of them developing surrounding edema. Annals of Emergency Medicine August “I like money, I have a little in a jar on my fridge. I want more money, that’s where you come in” Color-Coded Prefilled Medication Syringes Decrease Time to Delivery and Dosing Error in Simulated Emergency Department Pediatric Resuscitations Synopsis - This was a prospective, block-randomized crossover simulation study evaluating the use of color-coded prefilled medical syringes decreased medical errors and time to treat. The author has a pending patent using prefilled medical syringes that color coded using the Broselow Tape coloring coding scheme. Errors were made in 26% (95%CI 19-35%) of patients using the conventional method and 65% of those were considered critical errors. Errors were made in only 4% (95%CI 1-9%) when using the pre-filled color coded medicine syringes. Time from preparation to delivery was 19 seconds vs 47seconds using the color coded syringes vs conventional method as well. “Nothing like a contrast chaser to go with some abdominal pain” Use of Oral Contrast for Abdominal Computed Tomography in Children With Blunt Torso Trauma Synopsis - This was a secondary analysis using the PECARN dataset for blunt abdominal trauma evaluating the accuracy of identifying intra-abdominal injuries in children after blunt abdominal trauma using CT scans with IV contrast alone vs IV and PO contrast. 20% of patients received both IV and PO contrast and 80% received IV alone. 13% of patients with both had intra-abdominal injuries and 14% with IV contrast only. No significant differences were found in sensitivity of IV alone (97.7% 95%CI 96.1-98.8%) vs IV + PO (99.2% 95%CI 95.7-100%). Specificity for IV + PO was 84.7% (95%CI 82.2-87%) and IV alone was 80.8% (95%CI 79.4-82.1%) “What a pain in the neck” Can a Clinical Prediction Rule Reliably Predict Pediatric Bacterial Meningitis? Synopsis - This was a systematic review attempting to assess if there is a clinical guideline that would reliably identify patients with true bacterial meningitis. They found that cases of bacterial meningitis have significantly decreased since H. flu and S. Pneumonia vaccinations and most patients are ultimately diagnosed with aseptic meningitis after receiving empiric antibiotics. None of the articles found were able to reliably predict bacterial vs viral meningitis. LP and empiric antibiotics are still necessary while awaiting culture results. “Haven’t they heard of heal with steel” Can Children With Uncomplicated Acute Appendicitis Be Treated With Antibiotics Instead of an Appendectomy? Synopsis - This was a literature review that evaluated the use of non-operative management for uncomplicated acute appendicitis. They found that there was a 2.6-5.7% complication rate associated with non-perforated appendectomies. They found that 4 studies have been performed that have evaluated non-operative management as opposed to appendectomy. They found an initial failure rate using antibiotics alone of 6-25% and a 1 year failure rate of 19% (95%CI 7-43%). One study found a shorter out-of-school time with antibiotics vs appendectomy and appendectomy was not found to have a statistically significant absolute risk reduction. Journal of Trauma July “New study shows your head and your body probably shouldn’t go to the same hospital” Concordance of performance metrics among US trauma centers caring for injured children Synopsis - This was an observational study collecting data from 150 US trauma centers to evaluate center-level performance relative to peers is consistent across four performance metrics: in-hospital mortality, non-operative management of blunt splenic injury, use of ICP monitors after severe TBI, and craniotomy for children with severe TBI and associated subdural/epidural hematoma. Multivariable regression was used to obtain center-specific odds ratios comparing each quality indicator to mortality. They found that only three centers performed similarly in all four metrics. Overall there was a general lack of concordance among indicators with the greatest variety being seen with ICP monitoring. August “One dataset to rule them all” Management of children with solid organ injuries after blunt torso trauma Synopsis - This was a secondary analysis from a prospective observational study conducted by PECARN to determine solid organ injury that required acute intervention and disposition from the ED. They found that 5% had solid organ injury and splenic injuries were the most common. Isolated solid organ injuries were identified in 69% of these patients and treatment included: laparotomy 4.1%, angiographic embolization 1.4%, and blood transfusion 11%. Laparotomy rates were higher in free-standing children's hospitals. The rate of ICU admission was 9-73% and only 3% were sent directly home and an additional 4% had ED observation. There was a low rate of intervention associated with solid organ injuries and considerable variation in ED disposition, differing from published guidelines. Interestingly, they found that 75% of children with an isolated solid organ injury had intraperitoneal fluid but only 25% had a finding on FAST exam. “Sort of unsure why the pathway didn’t work, really unsure why you throw on the 1 yard line” Pediatric solid organ injury operative interventions and outcomes at Harborview Medical Center, before and after introduction of a solid organ injury pathway for pediatrics Synopsis - This was a retrospective chart review that attempted to compare the proportion of patients undergoing operative intervention before and after the implementation of a clinical pathway developed to standardize care of solid organ injury. Secondary outcomes included length of stay and mortality. They found that the proportion of patient with spleen injury undergoing splenectomy and the proportion of patients undergoing abdominal operative intervention did not change with implementation of a clinical pathway. They did find that institution of a clinical pathway decreased mortality among children with non-isolated injury as well as median length of stay. They were unsure if this could be attributed to the implementation of the clinical pathway. |

Pediatric EM BlogAuthorPediatric EM Fellows at CMC/Levine Children's Hospital. Archives

November 2016

Categories

All

Disclaimer: All images are the sole property of CMC Emergency Medicine Residency and cannot be reproduced without written consent. Patient identifiers have been redacted/changed or patient consent has been obtained. Information contained in this blog is the opinion of the authors and application of material contained in this blog is at the discretion of the practitioner to verify for accuracy.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed